-

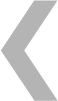

Untitled #126 (1964)

Wallace Berman

In June 1964, Wallace Berman discovered a commercial ad for a Sony transistor radio in an edition of LIFE magazine. He immediately seized on the handheld transmitter as his most pertinent image, inserting a cosmos of images clipped from various popular magazines. Machines, bodies, animals, buildings, plants, athletes, astronauts, musicians, actors, guns, esoteric symbols, stars, and inter-galactic explosions are but several of the many subjects he used. Over the years, Berman’s Verifax collages would appear in various incarnations: straight-forward radio-grids and a related series of large composite, brightly colored Shuffle pieces, Verifax combines, and mixed-media collages. Berman never intended the individual Verifax hand to be seen on its own. Like other isolated hands, this untitled collage is a posthumous fragment, found in the artist’s studio after his death. It is but a single building block in a complex visual syntax that endlessly assembled and reassembled signs in an attempt to disrupt habitual ways of seeing.

Single negative photographic image 6 1/2 x 7 in

Courtesy Estate of Wallace Berman and Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles -

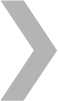

Untitled (date unknown)

Wallace Berman

Ancient languages, esoteric systems, and cryptic messages adrift in the airwaves have fascinated Wallace Berman since the early 1950s and lead to the creation of artworks that deliberately engaged notions of “code†and subliminal signification. Occult symbols and Hebrew letters appear frequently in his work, alluding to his interest in Jewish mysticism and Kabbalah, an arcane medieval practice that advocated the imaginative decoding of signs as a gateway to spiritual enlightenment. In this untitled and undated collage, chemical splashes radiate from an obscure circular symbol like emanations of a divine presence. The circle is inscribed at the center with a Masonic pyramid and the Aleph, first letter of the Hebrew alphabet and symbol for “himself/man, lord & master, […] the power of the single thrust, the pure gesture of self.†Berman had chosen the Aleph as his personal emblem, using it signature-style on many of his art works, even emblazoning it on his motorcycle helmet. The giant mushroom below eludes easy interpretation, but may well refer to the many mind-altering drugs that proliferated in Berman's circle.

Negative verifax collage 10 x 8 ½ in

Courtesy Estate of Wallace Berman and Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles -

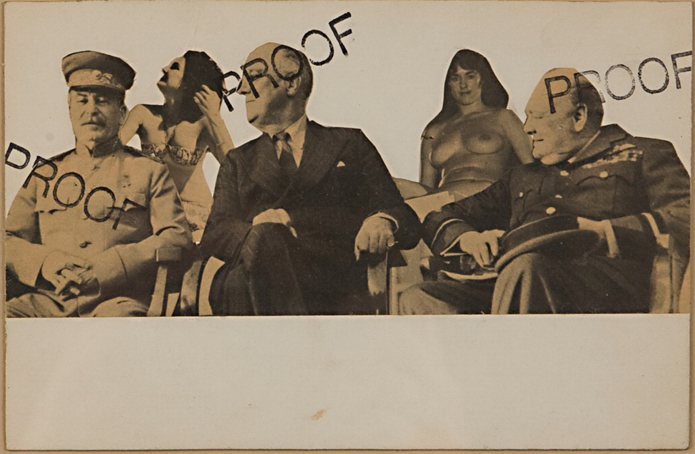

Untitled [Proof, Yalta and Broads in Beige] (date unknown)

Wallace Berman

Photography has long been considered a truthful witness to visual experience, offering indisputable evidence of what actually happened. Yet as the work of many artists since WWII has shown, the camera is not only a faithful recording device, but also an infinitely variable graphic tool, capable of rendering the world in entirely fictitious fashion. For this untitled Verifax collage, Wallace Berman clipped a press photograph of the famous 1943 Tehran Conference, showing General Secretary Josef Stalin, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill on the porch of the Soviet Embassy, where the meeting was held. In a sly and irreverent move, Berman pasted in two pornographic nudes behind the Allied leaders, presenting the image as irrefutable “proof” of the perversions and illicit transgressions he felt were endemic to wartime politics. The Tehran Conference was the first meeting between “The Big Three,” as they were known, to discuss final strategy in the war against Nazi Germany. They convened again little over a year later at Livadia Palace near Yalta in Crimea – a meeting that Berman mistakenly cites in the image’s subtitle. His error of sorts is a humorous reminder that few things are ever what they appear to be.

Verifax collage with proof stamp 5 x 7 1/2 in

Courtesy Estate of Wallace Berman and Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles -

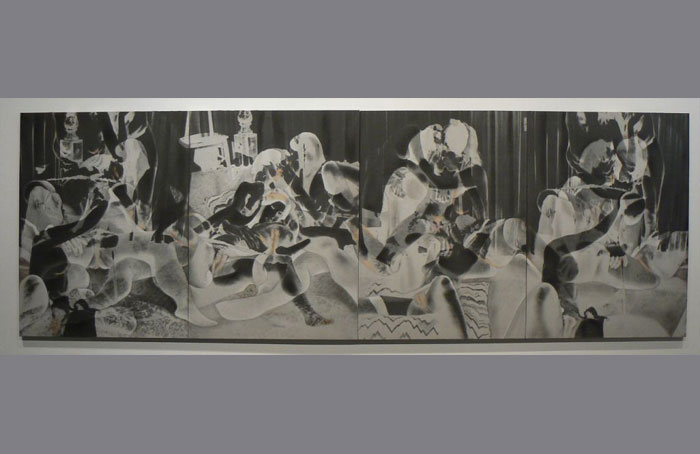

Different Strokes, 1970/97 (1970)

Robert Heinecken

From early on in his career, Robert Heinecken engaged unconventional processes and an irreverent approach to the photographic image that challenged everything the medium was supposed to be. Trained as a print-maker, he was attracted to photography for its “residual illusion of reality,” which he exploited for nearly four decades to powerful visual and conceptual ends. Heinecken frequently arranged his large-scale works in gridded compositions, using appropriated porn, superimposition, and a distinctively filmic arrangement of individual panels. As he explained in a 1996 Interview, Different Strokes of 1970 directly engages concepts of cinematic time: “So the first panel would be, let's say, made from a superimposition of A and B. The next one, which would be adjacent to it, would be B and C, and C and D, and so on, so that if you look at the structure of the picture it's really narrative from left to right. […] It's definitely a picture that leans on a film premise in that way.” The resulting multi-layered imagery yields its content only sequentially, unfurled and penetrated by the viewer in careful visual analysis.

Chalk and photographic emulsion on canvas 2 panels, 41 5/8 x 62 7/8 in

Courtesy Robert Heinecken Estate, Chicago, IL, and Cherry and Martin Gallery, Culver City. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer -

(from) Are You Rea (1964-68)

Robert Heinecken

Offset lithographs from a portfolio of 25 Various sizes, in 16 x 20 in frames

Collection Sam Mellon and Julie Deamer-Mellon, Los Angeles, California -

Untitled (Odd Couple Red Background) (date unknown)

Wallace Berman

For Wallace Berman, viewer participation and active physical interface with his art were critical concepts. Many of his art works reveal their meaning only with time, as viewers handle his mail art or mentally juggle the meaning of his Verifax collage in an effort to decipher their visual content. The idea of “gesture” and the artist’s hand as the dispenser of artistic meaning was equally important. The touch of his hand was often felt quite literally – in his early hand-built assemblages, in the torn papers and photographs affixed to his collages, in thickly painted backgrounds, in the do-it-yourself approach to his loose-leaf Semina publication, or in small images like this. Untitled (Odd Couple Red Background) belongs to a series of Faceless Faces works, which Berman created sporadically between 1963 and 1973. Taking advantage of the wet Verifax process, he rubbed out his subjects’ features before the ink had dried. This stark gesture of obliteration and defacement betrayed his disillusionment with contemporary celebrity and political culture.

Verifax collage 6 x 5 in

Courtesy Estate of Wallace Berman and Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles -

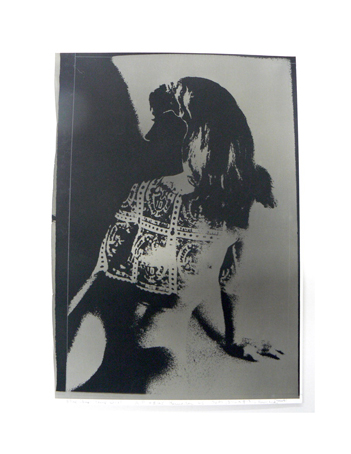

Blue Chip Stamp Girl (1965)

Robert Heinecken

Pornography and the female figure were key subjects for Robert Heinecken throughout his career. In Blue Chip Stamp Girl of 1965 he overlays a starkly solarized image of a mail order nude with a set of S&H Green Stamps obtained from a local supermarket, gas station, or department store. Distributed by the Sperry & Hutchinson company as parts of their retail rewards program, Green Stamps were popular in the United States from the 1930s until the late 1980s. Issued in denominations of one, thirty, or fifty points, these free stamps were available at checkout counters everywhere, collected by the customer in special “savers’ books” and redeemed for products from the local S&H store or sales catalog. Like the competing Blue Chip Stamps referred to in this title, Green Stamps enjoyed their greatest popularity in the 1960s, embodying the rampant consumerism and “save while you spend” ethos of the time. In Heinecken’s image, however, the juxtaposition of commercial trading stamps and mail order erotica makes subtler points, highlighting the veiled interdependencies of sex and American retail culture as they played themselves out every day in the market place.

Gelatin silver print Gelatin silver print 13 5/8 x 8 x in.

Courtesy Robert Heinecken Estate, Chicago, Illinois -

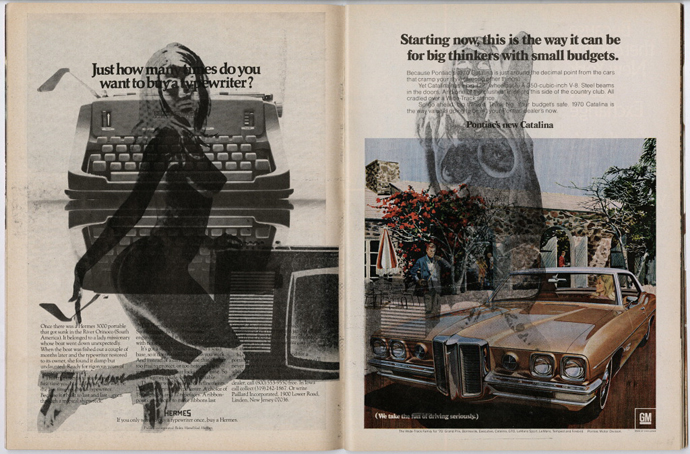

Periodical #1 (Periodical Pain) (2) (1969)

Robert Heinecken

In the late 1960s, Heinecken began taking illustrated magazines apart page by page, imprinting them with hardcore porn and reassembling them in new configurations he identified as “revised” or “compromised.” Between 1969 and 1974, he created nineteen such “mongrel publications,” in editions ranging from one to nineteen, none of them ever the same. Some of his magazines consist entirely of ads, overprinted with lithographs of leather-clad women in crassly sexual poses, alluding to the illicit desires and perversions fueled by modern-day consumerism. Others, like Periodical Pain, juggled clippings from 1969 editions of various popular magazines, like Glamour and Good Housekeeping, sharply exposing the hidden plots and manufactured experiences embedded in the contemporary press. Heinecken later observed that he regarded his magazines as evidence of alternative truths elicited by a secret operative: “I often envision myself as a bizarre guerilla, investing in a kind of humorous warfare in which a series of minimal, direct, invented acts result in maximum extrinsic effect, but without consistent rationale. I might liken it to the intention of making police photographs in which there is no crime involved—but with that assumption."

Artist bound and collated found magazine pages 10.75 x 8.5 in

Courtesy Robert Heinecken Estate, Chicago, Illinois, and Cherry and Martin Gallery, Culver City, California -

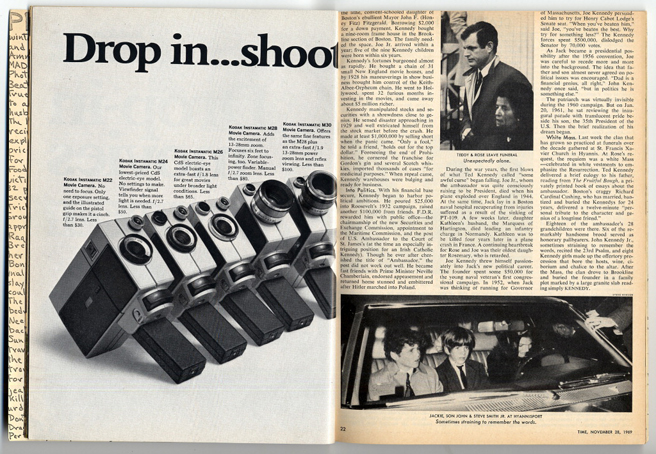

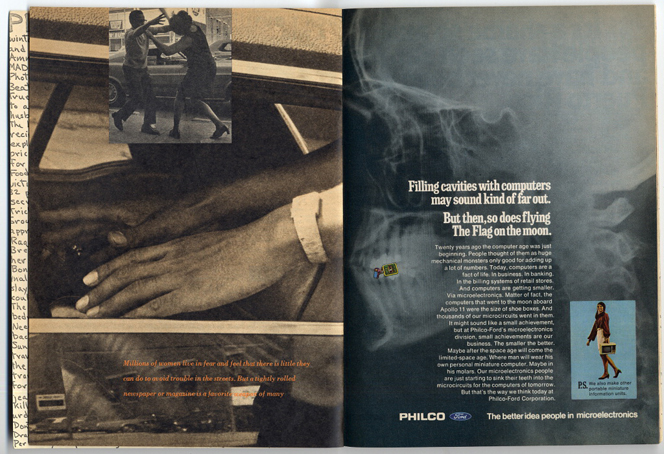

Periodical #1 (Periodical Pain) (1) (1969)

Robert Heinecken

In the late 1960s, Heinecken began taking illustrated magazines apart page by page, imprinting them with hardcore porn and reassembling them in new configurations he identified as “revised†or “compromised.†Between 1969 and 1974, he created nineteen such “mongrel publications,†in editions ranging from one to nineteen, none of them ever the same. Some of his magazines consist entirely of ads, overprinted with lithographs of leather-clad women in crassly sexual poses, alluding to the illicit desires and perversions fueled by modern-day consumerism. Others, Periodical Pain, juggled clippings from 1969 editions of various popular magazines, Glamour; Good Housekeeping, sharply exposing the hidden plots and manufactured experiences embedded in the contemporary press. Heinecken later observed that he regarded his magazines as evidence of alternative truths elicited by a secret operative: “I often envision myself as a bizarre guerilla, investing in a kind of humorous warfare in which a series of minimal, direct, invented acts result in maximum extrinsic effect, but without consistent rationale. I might liken it to the intention of making police photographs in which there is no crime involved—but with that assumption."

Artist bound and collated found magazine pages 10.75 x 8.5 in

Courtesy Robert Heinecken Estate, Chicago, Illinois, and Cherry and Martin Gallery, Culver City, CA -

Time (1st Group) (1969)

Robert Heinecken

Re-collated and re-bound found magazine with offset lithography 11 x 8 in

Courtesy Robert Heinecken Estate, Chicago, Illinois, and Cherry and Martin Gallery, Culver City, California -

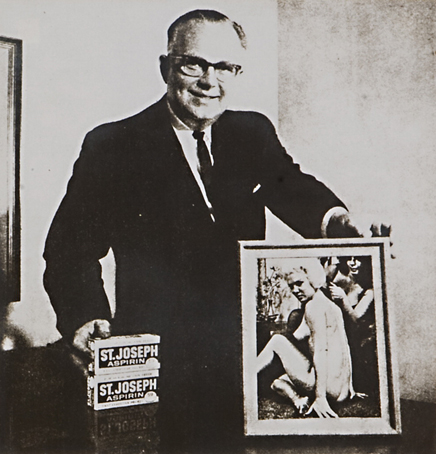

Untitled (Businessman) (1964)

Wallace Berman

In late 1963, around the time of President John F. Kennedy's assassination, Berman embarked on a new body of artwork made with a friend's old Verifax copier, a precursor to the Xerox machine. Built on materials appropriated from the illustrated press, the new work owed much to Marcel Duchamp's revolutionary idea of the Readymade and eventually engendered Berman's most signature image: a hand-held transistor radio, inlaid with found pictures and arrayed in grids ranging from four to sixty-four hands at a time. Before adopting the radio as his most defining motif, however, Berman experimented with verifaxed pictures of salesmen and corporate executives, slowly honing in on popular broadcasting systems as his key interpretive metaphor. This untitled Verifax collage from 1964 slyly pairs an Aspirin ad with an image culled from a pornographic magazine, highlighting corporate excesses and the illicit desires nurtured by 1960s American advertisement.

Single positive photographic image 6 ¾ x 5 in

Courtesy Estate of Wallace Berman and Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles

Armory Center for the Arts

Speaking in Tongues: The Art of Wallace Berman and Robert Heinecken

Speaking in Tongues advances our understanding of two seminal Los Angeles artists by bringing them into close conversation for the first time, examining how they both bridged modernist and emerging post-modernist trends by ushering in the use of photography as a key element of contemporary art. Placing Berman and Heinecken in the cultural context of 1960s and 1970s Southern California, which fueled and amplified their creative approaches, the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue trace the evolution of a new visual language, which placed photography and its representational contingencies at the heart of contemporary art.

Pasadena, CA 91103