The Getty Center

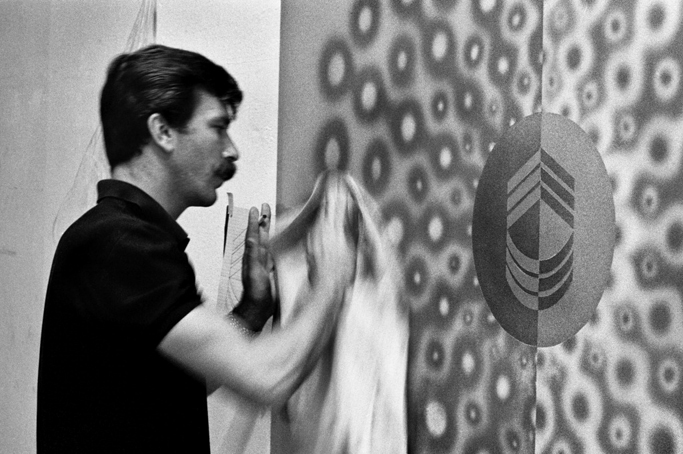

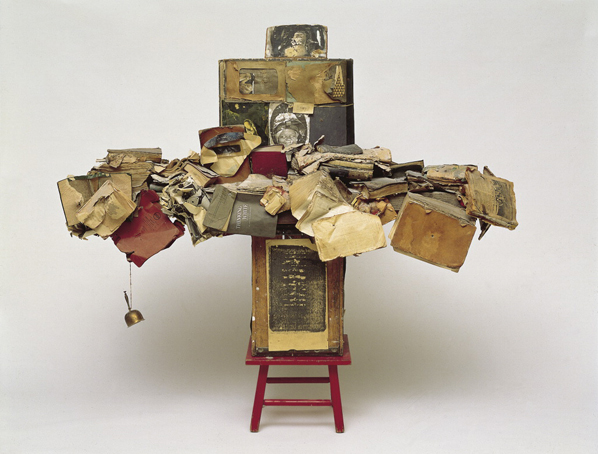

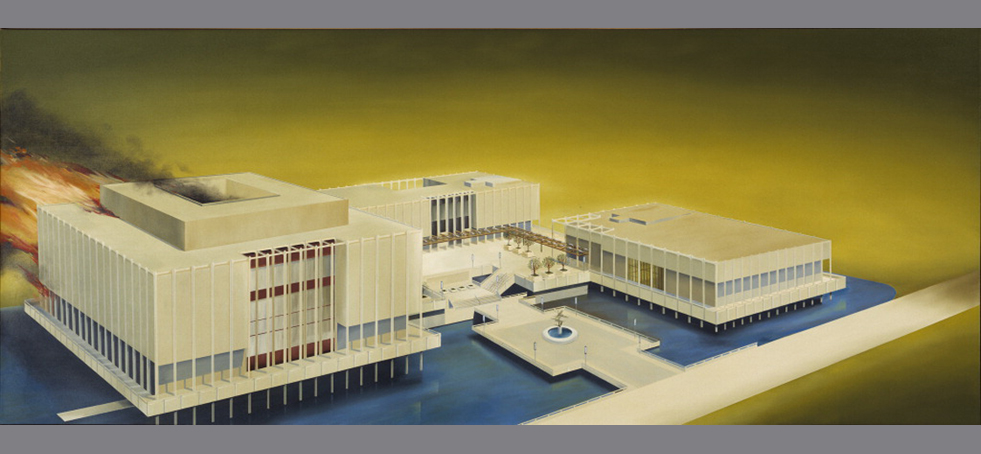

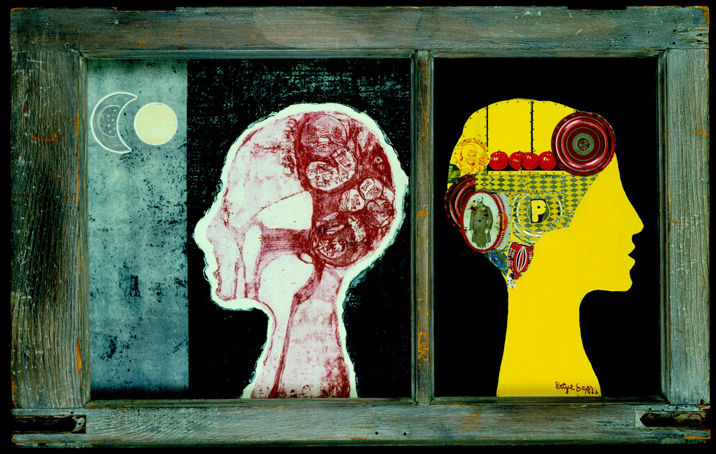

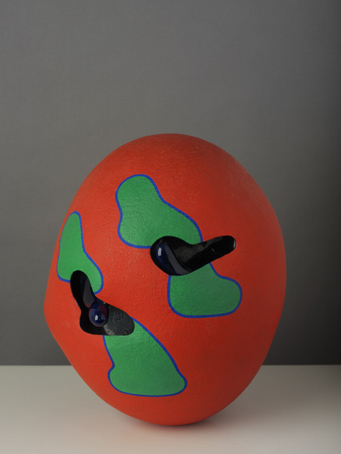

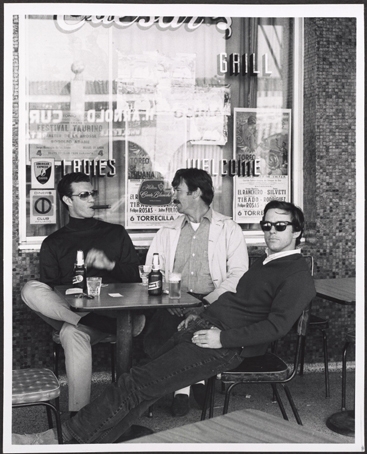

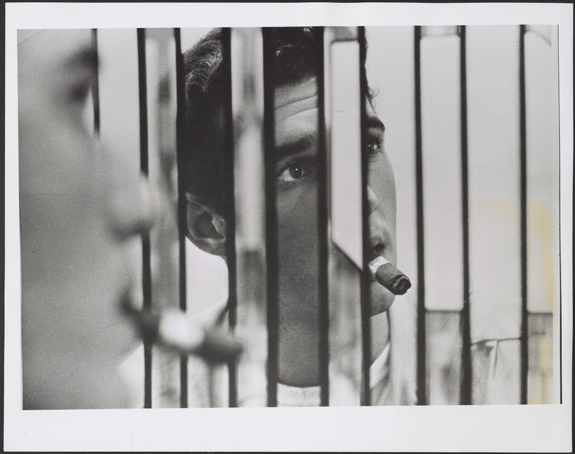

Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture, 1950-1970

The culmination of a nine-year research initiative organized by the Getty Research Institute, Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Paintings and Sculpture presents a focused examination of painting and sculpture produced in Southern California from the late 1940s to the early 1970s. Drawing from archival collections acquired by the Getty and sources that have become newly accessible as a result of the initiative, the exhibition will offer a fundamental reappraisal and reinterpretation of postwar Los Angeles art. The exhibition will feature nearly 50 artists and will include multiple works from each, on loan from preeminent national and international collections, allowing visitors to get a sense of the distinctiveness of individual practices as well as the place of Southern California artists within broader historical movements. This exhibition is co-organized by the Getty Research Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum and will travel to the Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin in the spring of 2012.

Los Angeles, CA 90049