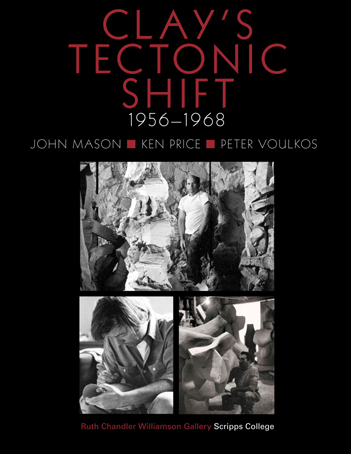

Untitled Sculpture (1956)

Peter Voulkos

“For centuries, clay was considered almost solely a medium for functional objects and judged by different criteria than sculpture or painting. In the mid-1950s Peter Voulkos (1924–2002) began experiments in clay that transcended previous formal limitations on the medium, claiming it as a viable material for sculpture. Untitled (1956), for example, resembles an organism from a sci-fi fantasy, with its strange tendril-like markings and stacked bulbous forms seeming light years away from the world of salad bowls and tea services.” (Michael Duncan, “How Clay Got Cool: Setting the Stage for Peter Voulkos’s Radical Shift,” Clay’s Tectonic Shift Untitled, 1956, is an example of Voulkos’s combination of painting, sculpture, and pottery with the aesthetic sensibility inspired by Zen and Abstract Expressionism. Rather than the perfect smooth finish of craft ceramics, Voulkos has created an asymmetrical vessel with odd bulges and protruding slabs slapped on the surface. A uniform glaze is eschewed in favor of sweeping lines hearkening to the spontaneous calligraphy of Zen.

Stoneware, glazed 30.5 x 14.5 x 14.75 in

Private Collection, Berkeley, California. Photograph by Schopplein.com © Voulkos & Co. Catalogue Project

Untitled Vertical Sculpture (1960)

John Mason

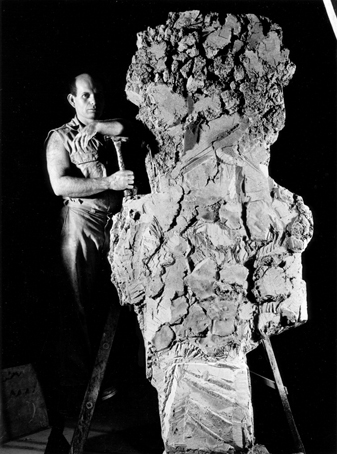

“Mason’s vertical sculptures began to develop as he discovered new ways to form clay. Instead of slamming it down on the floor, as he had done with the material for the Blue Wall in 1959, Mason began to build around a central axis, in a straightforward and simple fashion. There is a palpable sense of the discovery of this method and the strikingly totemic vertical sculptures that he began to produce. . . . The work in the exhibition, Untitled Vertical Sculpture, 1961, is an example of these primal, almost vertebrate works. These pieces have a kind of mass that is also representative of energy, or perhaps growth. Their evocation of some kind of primordial world, without a direct figurative reference, marks them as formal investigations—but with a mysterious presence.‘I compacted clay around an armature—a wooden member,’ recalled Mason. ‘I figured out how to do that and to be able to remove the wood after it reached a partially dried state, a leather state. I could build these forms, which I call vertical sculptures, and they had very interesting surfaces as the result of my manipulating the clay. So I did . . . probably pretty close to a dozen’” (Frank Lloyd, “Vanguard Ceramics: John Mason, Ken Price, and Peter Voulkos,” in Clay’s Tectonic Shift, exh. cat. [forthcoming]).

Stoneware 63 1/2 x 14 x 14 in

Private Collection, Los Angeles. Photograph by Anthony Cunha © John Mason

Geometric Form—Dark (1966)

John Mason

“Eventually, Mason refined the form to a primal, mysterious geometric form. The huge rectangular block titled Geometric Form—Dark, 1966, is the most simplified of Mason's large-scale sculpture. Mysterious in its presence, the single-color monolith draws attention to its mass by the surface coloration. The work is reductive, yet powerful, considering that the artist has simply described them as ‘really very blocky, flat surfaces.’ The sculptures must be experienced physically, and their mysterious presence is directly related to their mass, yet they are of human height†(Frank Lloyd, “Vanguard Ceramics: John Mason, Ken Price, and Peter Voulkos,†in Clay's Tectonic Shift, exh. cat. [forthcoming]).

Ceramic 59 x 43 x 25 in

Collection of Robinson Family, Sausalito. Photo: Anthony Cunha © John Mason

Untitled (Mound) (ca. 1967)

Ken Price

Price’s Mounds series drew on the primitive, organic forms of lumps and humps. In Untitled (Mound), ca. 1967, the organic nature of the piece is further enhanced by the green protrusion incised with blue sausage shapes, similar to enlarged worm tracks or bacterium in primordial ooze.

Fired clay with acrylic and lacquer 5 3/4 x 8 3/4 x 4 1/2 in

Collection of Joan and Jack Quinn. Photograph by Anthony Cunha © Ken Price

Untitled Wall Relief (1960)

John Mason

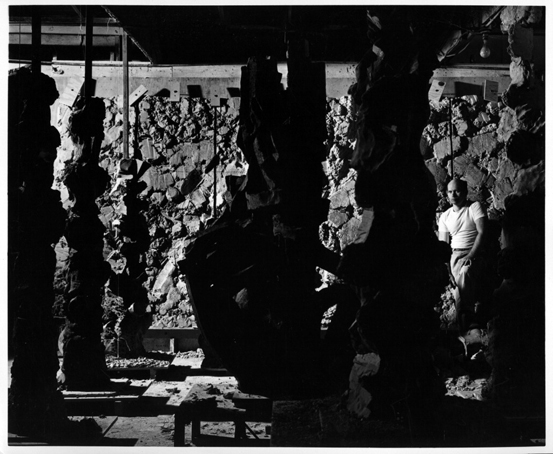

The studio Mason shared with Voulkos on 2101 Glendale Boulevard gave the artists space to create large-scale ceramic sculpture. On an approximately 12 x 50 feet “mounting wall,” Mason used strips and chunks of clay to construct his wall reliefs and built custom steel supports on which to hang them. Although seemingly similar to architectural ceramics, Mason’s wall reliefs were not commissioned. When asked by studio visitors, “How are you going to sell it?,” he replied, “I don’t know.”

Ceramic with glazes 35 1/2 x 45 3/4 x 3 in

Collection of Alan Mandell. Photograph by Anthony Cunha © John Mason

Untitled (1959)

Ken Price

This example of Price’s earlier work shows the emergence of the nonfunctional mound form and Price’s preoccupation with color. Here, he continues to use earth-toned traditional ceramic glazes; as his career progresses, he gains fame from his use of brilliant color in industrial lacquers and acrylics.

Glaze ceramic 21 1/2 x 20 x 20 in

Collection of James Corcoran Gallery. Photograph by Anthony Cunha © Ken Price

Sitting Bull (1959)

Peter Voulkos

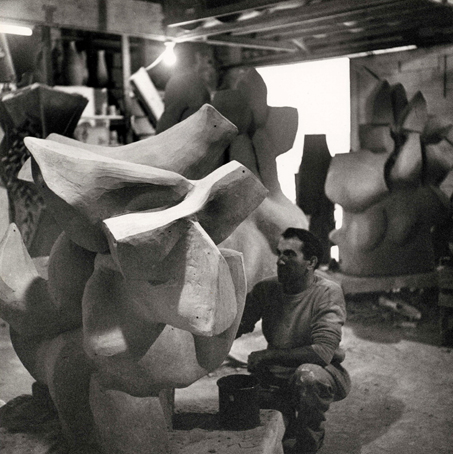

In 1957 Peter Voulkos and John Mason moved into a studio on 2101 Glendale Boulevard and commissioned Mike Kalan, a designer of industry kilns, to build one of the largest noncommercial kilns on the West Coast, enabling the artists to fire pieces at a scale heretofore unprecedented in ceramic sculpture. Nearly 6 feet tall, the bulging muscularity of Sitting Bull defied the conventional view of ceramics as a medium for delicate saucers and teapots. The looming sculpture commands attention and lays claim to the space around it; yet rather than seeming ponderous, it stands poised as if ready to leap into action. Sitting Bull was exhibited in Voulkos’s second solo exhibition at Landau Gallery in 1959.

Stoneware, wheel-thrown and paddled parts, slip and glaze 69 x 37 x 37 in

Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Bequest of Hans G. M. de Schulthess. 1965.16. Photograph by Brian Forrest © Voulkos & Co. Catalogue Project

Untitled (Monolith) (1964)

John Mason

In 1963 Mason returned to the X form he first explored in his X-Pot series of 1957, but this time he simplified the forms to minimalist geometric shapes while preserving the massive scale of his wall reliefs and vertical sculpture. “Made in 1964, a free-standing monolith (Untitled, 1964) is an example of the totemic series that followed the first massive wall. The striking, angular glazed ceramic piece with six protruding arms, now had an opening, something new. This first one was vertical, standing 66 inches high, making the transition from the walls to a simplified primary shape.” (Frank Lloyd, “Vanguard Ceramics: John Mason, Ken Price, and Peter Voulkos,” in Clay’s Tectonic Shift, exh. cat. [forthcoming])

Stoneware with glaze 66 1/2 x 64 x 17 in

Collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Gift of the Women's Board. 71.68 © John Mason

L. Red (1963)

Ken Price

“The largest and most lustrous lacquered egg in our show, L. Red, 1963, is somewhat more vertical, and the opening is above the meridian of the orb. On this work, Price did not use lines, but described shapes in an intense, deep magenta. These are excellent examples of the work from this time period” (Frank Lloyd, “Vanguard Ceramics: John Mason, Ken Price, and Peter Voulkos,” in Clay’s Tectonic Shift, exh. cat. [forthcoming]).

Stoneware with lacquer and acrylic 13 1/2 x 12 x 10 in

Collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund purchase. 82.155 © Kenneth Price

Tientos (1959)

Peter Voulkos

For our exhibit, the example Tientos, 1959, shows how Voulkos built a vertical form and incorporated the paddled shapes with various volumes and torn slabs. As his working methods evolved, he brought together the process and the material in a raw, physical sculpture. These works were clearly a new use of the material, and pushed the possibilities for fired clay. Formed by stacking and joining bold forms, the work had an aggregate and primal power. It seemed at once primitive, totemic and yet forged of a modern sensibility.” (Frank Lloyd, “Vanguard Ceramics: John Mason, Ken Price, and Peter Voulkos,” Clay’s Tectonic Shift exhibition catalog)

Clay with iron glazes 55 x 19 x 30 in

Collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Purchase through a gift of Phyllis Wattis, and gift of Gregory LaChapelle. 98.28 © Estate of Peter Voulkos

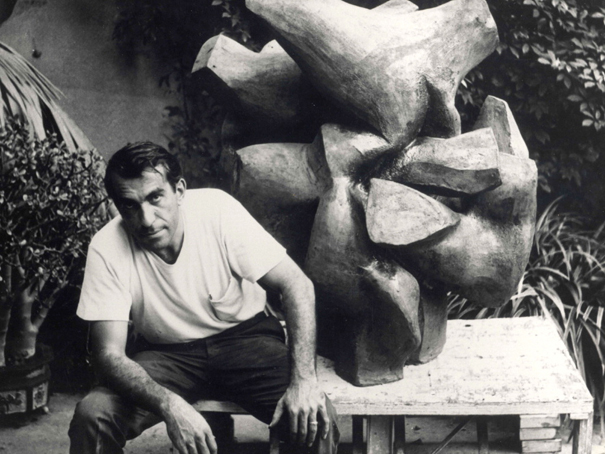

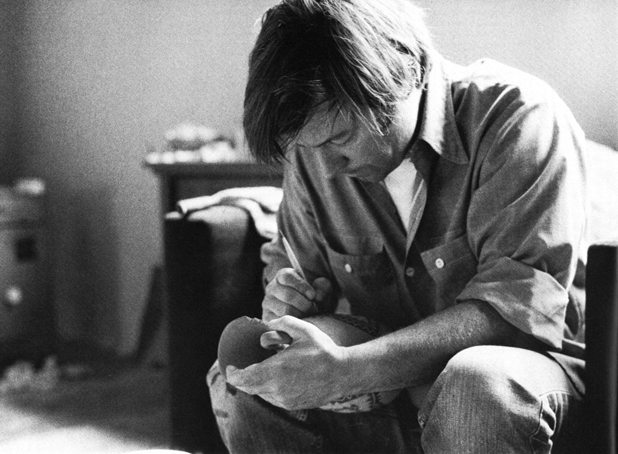

Installation at Ferus Gallery Patio (1957)

John Mason

Photograph by John Mason © John Mason

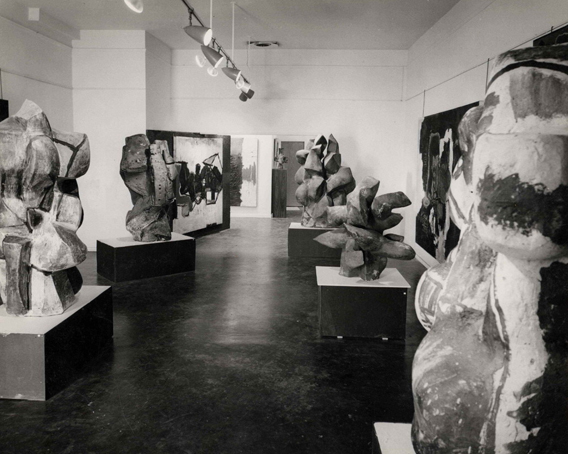

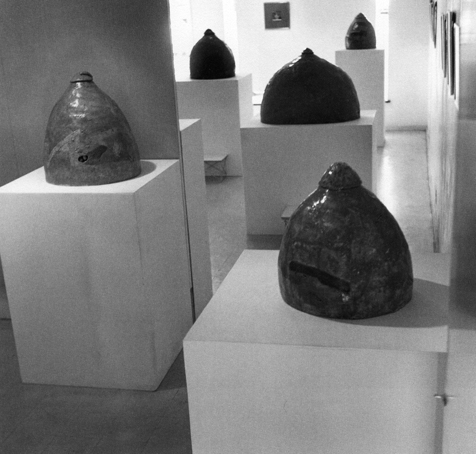

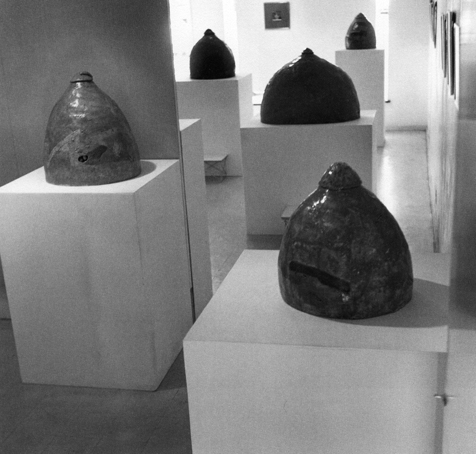

Installation view of Ken Price's first solo exhibition at Ferus Gallery (1960)

Ken Price

Photograph by Seymour Rosen