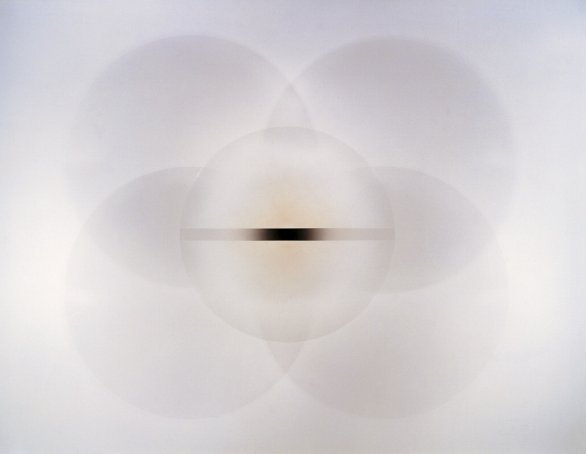

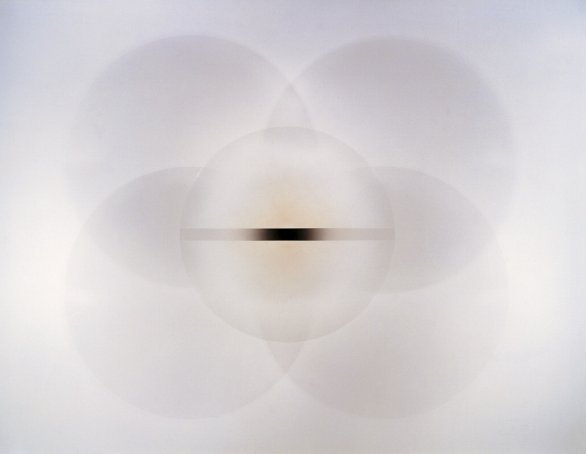

Klenator Draculas (1977)

Billy Al Bengston

"The process of making a painting is the process of living. . . . When it’s all over, he has made a diary about his life."—Billy Al Bengston

After his first solo show at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in 1958, Billy Al Bengston soon became a fixture in what became known as the Cool School group of young Los Angeles artists. In his works Bengston typically depicts a single, simple, isolated subject in a range of materials and methods that often reflect the environments and times he has encountered in his travels. The Dracula series, which he began in the 1970s, focuses on the soft and pliable form of a delicate iris flower. The shifting circles of color in Klenator Draculas are meant to suggest rippling pools of light moving in water.

Acrylic on canvas 60 x 56 1/8 in

Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation © Billy Al Bengston

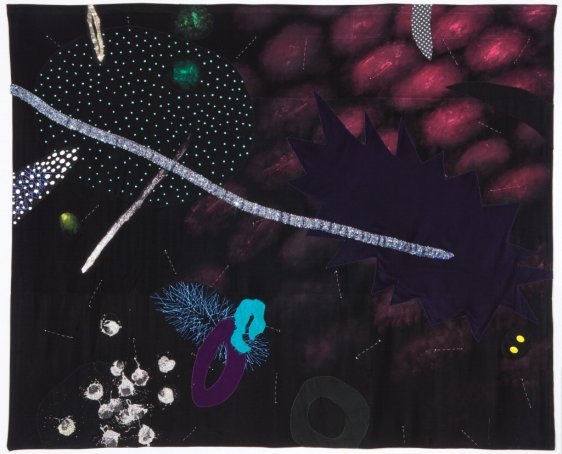

Dabs (1982)

Carol Shaw-Sutton, Joan Austin

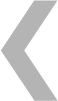

Southern California artist Peter Alexander explored light, color, and decorative surface effects in his glittering, sequined works of the 1980s. In Dabs Alexander creates a textured scene that resembles the vibrancy of life in the depths of the ocean. Originally associated with the Light and Space movement, Alexander shows that luminosity and brilliance occur even in the darkest places one can imagine. His method references crafting, such as appliqua © and embroidery, and his use of kitschy materials like glitter and sequins only serve to heighten the effect. Here Alexander retains his interest in the properties of light, yet calls attention to the type of velvet painting reminiscent of tourist art from Mexico as a potential form of high art.

Acrylic and fabric on velvet 87 x 104 in

Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation

American Standard (1975)

Charles Arnoldi

Los Angeles artist Charles Arnoldi first came to prominence in the early 1970s with a series of twig paintings and sculptures, flat designs made from actual tree branches arranged to echo the expressive lines of modern drawing. American Standard is one of the earliest examples of these works. This eclectic and inventive approach to sculpture was initially aligned with 1970s conceptualism, which proclaimed traditional artistic methods obsolete. Through his use of tree branches as art materials, Arnoldi made a conceptualist gesture—a kind of natural readymade—while paying homage to the intrinsic beauty of natural forms.

Painted Wood Construction 20 x 20-1/2 x 2 in

Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation © Charles Arnoldi

Impound (1985)

Charles Arnoldi

Wood has been part of Charles Arnoldi's oeuvre since the late 1960s. Impound is part of his Logjam series—paintings inspired by images of Mount St. Helen's volcanic eruption in 1980, which sent a mudslide of timber cascading down the mountainside in wild disarray. In this work Arnoldi uses a diptych format to re-create an impression of the volcanic explosion and its aftermath. On the left, he constructs a painted relief made by actually cutting into a wood panel with a chainsaw. A thousand abstract “sticks†seem to implode and explode both toward and away from the viewer. He then juxtaposes this artist's rendering with the panel on the right, where he creates a more naturalistic sculptural surface composed of layers of actual tree branches.

Acrylic and branches on plywood 92 x 154 x 11 in. (four panels)

Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation © Charles Arnoldi

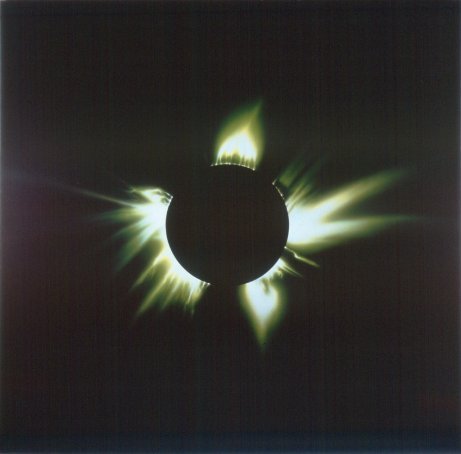

Untitled (1983)

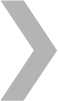

Jack Goldstein

Jack Goldstein achieved success in New York in the late 1970s for his performance, film, and sound-recording works that explored the relationship between human subjectivity and technology. In the early 1980s, Goldstein turned toward the more traditional realm of painting in works such as Untitled (1983), creating images that depict the realm of nature—landscape, space, or topographical maps—seen by and through layers of technological manipulation that recall his earlier performances. Goldstein created his paintings by appropriating found images from scientific and technological magazines, and then enlarging, segmenting, and painting the source image with an intricate airbrush technique. Untitled is an image of a telescopic view of a solar eclipse.

Acrylic on canvas 96 x 96 in

Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation © The Estate of Jack Goldstein

Untitled (1968)

Robert Irwin

Acrylic lacquer on plastic Height: 24 in; diameter: 54 in

Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation California Art: Selections from the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation

Untitled (1985)

Ed Moses

"I’m interested in discovering things through the meandering and chaos in the confusion of painting."—Ed Moses

For his first exhibition in 1969 in Los Angeles, artist Ed Moses dislodged the roof and ceiling of the gallery, revealing the wood slats in between. Natural light streaming through these slats created shadows of diagonal patterns that shifted across the walls and floor of the gallery with the sun's movement. The shifting diagonal grid was also evident in paintings from the same exhibition. Throughout his career, the highly reductive grid, symbol of rationality and control, has continued to serve as the basic structuring device of his paintings. It is often paired with a loose, fluid use of paint, as in Untitled, where spreading stains of color and animal forms (spiders) swarm beneath a black grid.

Watercolor on paper 59 1/2 x 40 x 1 in

Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation © Ed Moses

Untitled (1973)

Tom Wudl

Tom Wudl first came to prominence in the early 1970s through his series of abstract paintings made from perforated rice paper. His nontraditional materials and colorful, flat surface patterns were typical of Los Angeles art of the time. This work's majestic size, reminiscent of nineteenth-century landscape or history painting, envelops the viewer in an abstractly rendered skyscape. The blue and white background represents the heavens. Two round shapes schematize stars or planets. A yellow bolt recalling lightning zigzags across the canvas. These elements culminate in a storm designed to evoke the mythic or religious symbolism of the sky as a place of cosmic creation. At the same time, by balancing this dramatic scene with a precise, controlled geometry, the seeming randomness of nature is shown to have an underlying mathematical structure.

Mixed media 70 x 90 in

Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation © Tom Wudl